When Jim and Dwight Crossed Paths

On a crisp November afternoon in 1912, two men who would become towering figures in American history collided on the football field at West Point. One was Jim Thorpe, the Sac and Fox Nation athlete already hailed as the greatest all-around sportsman of his era. The other was Dwight D. Eisenhower, a determined 22-year-old West Point cadet who would later command the Allied forces in World War II and serve as the 34th President of the United States. Their single encounter on November 9, 1912, became one of the most symbolic moments in American sports history—a clash between Indigenous brilliance and military tradition.

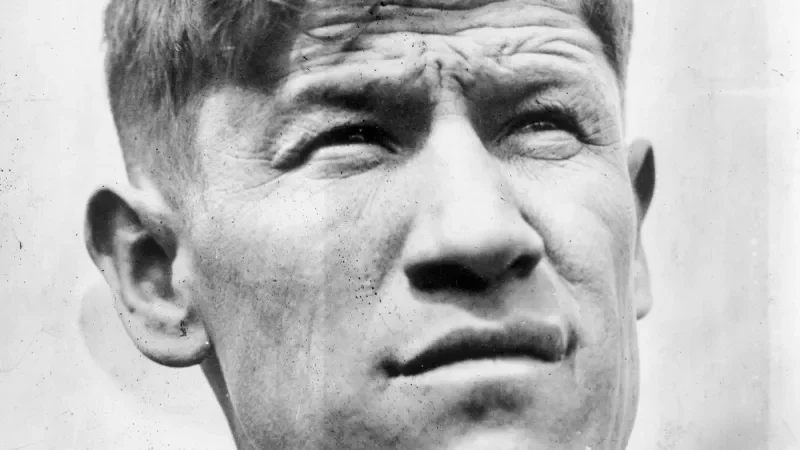

Jim Thorpe, born Wa-Tho-Huk ("Bright Path") in 1887 in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma), had just returned from the Stockholm Olympics, where he won gold medals in both the pentathlon and decathlon. Fresh off that triumph, Thorpe was starring for the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, a federal boarding school designed to assimilate Native children. Under legendary coach Pop Warner, the Carlisle Indians revolutionized football with speed, deception, and the forward pass. Thorpe, playing halfback, was the undisputed star—versatile, powerful, and nearly impossible to tackle.

Across the field stood the United States Military Academy at West Point. The Cadets boasted a strong team that included several future generals. Eisenhower, a junior halfback and linebacker known for his aggressive tackling, was eager to prove himself. West Point represented the pinnacle of American military discipline and national power. For many cadets, the Carlisle game carried extra weight: it pitted the future leaders of the U.S. military against Native Americans whose tribes had been defeated in the Indian Wars only a generation earlier.

The game itself was a stunning upset. Carlisle dominated Army 27–6. Thorpe was unstoppable. He scored two touchdowns, kicked four extra points, and was a defensive force. Eyewitness accounts describe Thorpe repeatedly breaking through the Army line “as if it was an open door.” In one memorable sequence, Eisenhower and another cadet, Charles Benedict, converged on Thorpe in an attempt to bring him down. Both Cadets collided violently while lunging at the elusive Thorpe. Eisenhower suffered a serious knee injury that ended his football career and nearly derailed his military ambitions. He was carried off the field, watching the rest of the game from the sidelines.

Thorpe’s performance that day was legendary. The Carlisle Indians, once dismissed as underdogs, had beaten a heavily favored Army squad in front of thousands of spectators, including high-ranking officers. Newspapers across the country celebrated the victory, with headlines proclaiming “Thorpe Beats the Army.” The game became a powerful symbol: a Native athlete, product of an assimilationist boarding school, had outplayed and outsmarted the nation’s future military elite.

Years later, Eisenhower never forgot the encounter. As President in 1961, he reflected on Thorpe in a speech: “Here and there, there are some people who are supremely endowed. My memory goes back to Jim Thorpe. He never practiced in his life, and he could do anything better than any other football player I ever saw.” Eisenhower’s admiration was genuine and enduring. He regarded Thorpe as one of the greatest natural athletes he had ever witnessed.

Their brief intersection carries deep historical resonance. In 1912, the United States was still grappling with the aftermath of the Indian Wars and forced assimilation policies. Carlisle itself embodied the federal government’s attempt to “civilize” Native children by erasing their cultures. Yet Thorpe’s excellence on the field challenged those assumptions. His victory over Army—symbol of American military might—became a quiet act of Indigenous resistance and pride.

For Eisenhower, the experience may have instilled lasting respect. As Supreme Allied Commander and later President, he led a nation that increasingly recognized the contributions of Native Americans, including the famed Code Talkers of World War II. The 1912 game foreshadowed broader themes in American history: the tension between conquest and admiration, between erasure and excellence.

Today, the story of Jim Thorpe and Dwight Eisenhower remains a compelling footnote in both sports and presidential history. It reminds us that greatness can emerge from the most unexpected places, and that even brief encounters can leave indelible marks on those who witness them.