From Barrio to National Icon: Gonzales and the Chicano Era

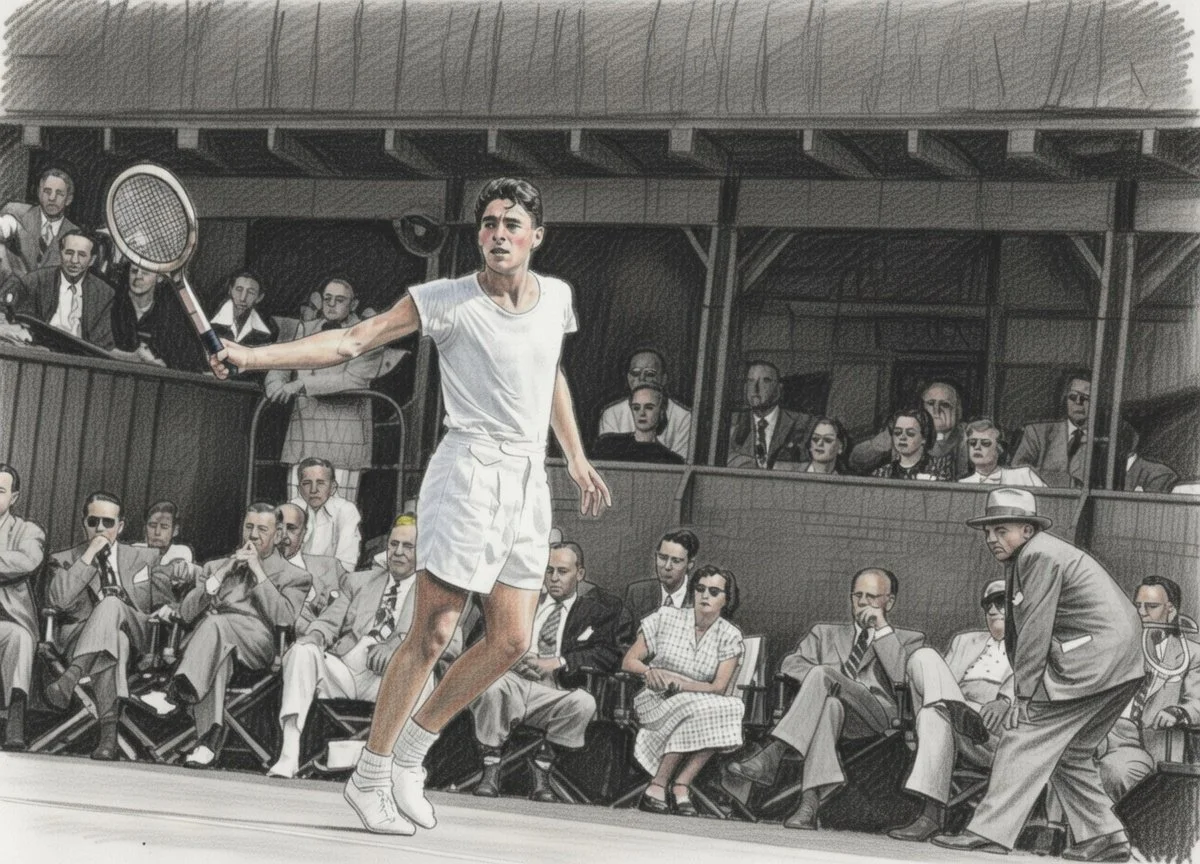

In the summer of 1948, a tall, fiery 20-year-old from the barrios of East Los Angeles stepped onto the grass courts of Forest Hills and stunned the tennis establishment. Richard Alonzo “Pancho” Gonzales, the son of Mexican immigrants, defeated the heavily favored Eric Sturgess in the final of the U.S. National Championships (now the US Open) to win his first major title. The following year he defended his crown. Gonzales wasn’t just winning matches—he was breaking through the invisible color line of American tennis, becoming the first Mexican-American superstar in a sport long reserved for the white, wealthy elite. His rise marked a cultural turning point, helping shift tennis from an exclusive country-club pastime into a more accessible, diverse, and passionate American spectacle.

Born on May 9, 1928, in Los Angeles to Mexican-American parents, Gonzales grew up in a modest neighborhood near the Los Angeles River. His father worked as a house painter; his mother was a seamstress. Tennis was not part of the family tradition—Pancho first picked up a racket at age 12 on the cracked public courts of Exposition Park. Largely self-taught, he developed a powerful serve and aggressive baseline game that would later define him. Expelled from high school after repeated truancy, Gonzales joined the Navy at 17, where he honed his game on military courts. Upon discharge, he quickly dominated Southern California junior tournaments, catching the eye of Perry T. Jones, the powerful head of the Southern California Tennis Association.

Despite facing subtle and overt discrimination—many clubs initially resisted allowing Mexican-Americans on their courts—Gonzales forced his way into the national amateur circuit. His 1948 and 1949 U.S. Nationals victories made him an instant celebrity, especially among Mexican-American communities in California, Texas, and the Southwest. For the first time, Latino families saw one of their own celebrated as America’s champion. Newspapers began calling him “Pancho” (a nickname he initially disliked but later embraced), and his story resonated deeply during the post-WWII era of growing Mexican-American civil rights activism.

In 1949, Gonzales turned professional, entering the barnstorming pro circuit dominated by legends like Jack Kramer and Pancho Segura. For the next two decades, he reigned as the world’s top professional player. He won the U.S. Pro Championship eight times (1953–1961) and claimed multiple Wembley and French Pro titles. His greatest moment came in 1969 at Wimbledon, when the 41-year-old Gonzales battled 25-year-old Charlie Pasarell in a legendary five-set, 112-game match—the longest in Wimbledon history at the time—winning 22-24, 1-6, 16-14, 6-3, 11-9. The match, played over two days, showcased Gonzales’ legendary stamina, competitive fire, and showmanship.

Gonzales fundamentally changed American tennis culture in several ways. First, he democratized the sport. Coming from public courts rather than private clubs, he proved that tennis greatness could emerge from working-class and minority communities. Second, he injected passion and personality into a traditionally reserved sport. Known for his explosive temper, fist-pumping celebrations, and intimidating presence, Gonzales brought an emotional intensity that foreshadowed the styles of Jimmy Connors and John McEnroe. Third, he became a powerful symbol of Mexican-American pride. During the Chicano Movement of the 1960s and 1970s, Gonzales was embraced as a cultural hero, representing resilience against discrimination and assimilation.

His influence extended beyond the court. He helped popularize tennis on television and opened doors for future Latino stars including Mary Joe Fernández, Gigi Fernández, and later players like Monica Puig and Coco Gauff (of mixed heritage). Gonzales’ success challenged the perception that tennis was exclusively a “white sport,” accelerating its growth in diverse urban communities.

Pancho Gonzales was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame in 1968. He passed away in 1995 at age 67, but his legacy lives on. Today, as tennis continues to diversify globally, Gonzales is remembered not only for his titles (he won an estimated 113 professional tournaments) but as the trailblazer who proved a Mexican-American kid from East LA could conquer what was once an elite Anglo domain.