Wa-Tho-Huk's Triumph: Jim Thorpe as the Enduring Symbol of Native Resilience and Pride

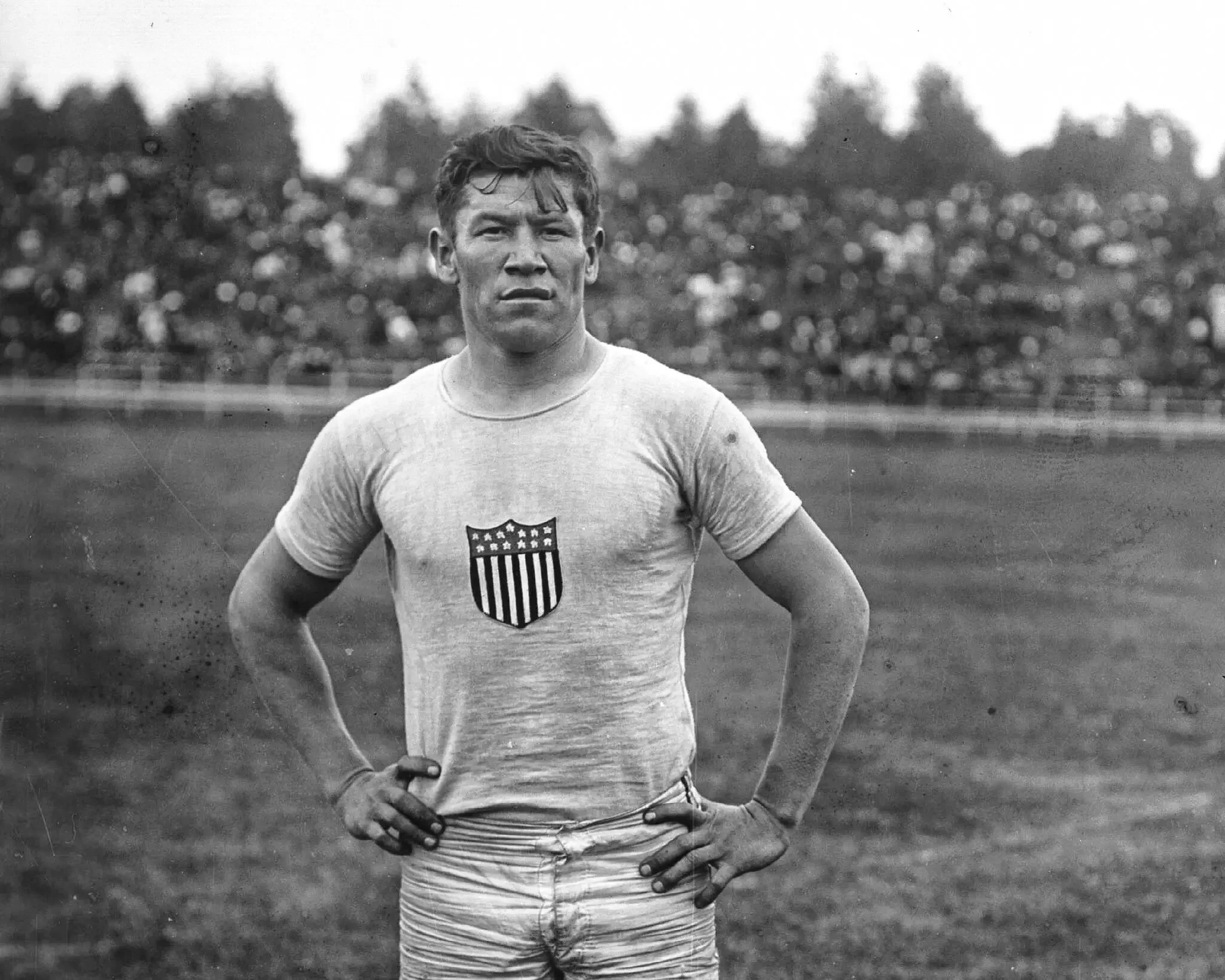

In the historic Stockholm stadium of 1912, amid the pageantry of the Fifth Olympiad, a young Native American from the Sac and Fox Nation shattered the world's expectations. Jim Thorpe, clad in mismatched shoes after his own were stolen, dominated the pentathlon and decathlon, earning two gold medals and the praise of Sweden's King Gustav V, who declared him "the greatest athlete in the world." This wasn't just athletic prowess; it was a defiant assertion of Native resilience in an era of forced assimilation and cultural erasure. Thorpe, often hailed as the 20th century's supreme athlete, transcended sports to become a symbol of American complexity—embodying the nation's promise while exposing its prejudices. His life, marked by triumphs, tragedies, and eventual vindication, intersects with U.S. history, geopolitics, and culture, influencing everything from Native identity to the professionalization of sports in a rapidly modernizing America.

Born Wa-Tho-Huk, or "Bright Path," on May 28, 1887 (or 1888, records vary), near Prague in Indian Territory (now Oklahoma), Thorpe was of Sac and Fox, Potawatomi, and Kickapoo descent. His parents, Hiram Thorpe (Sac and Fox) and Charlotte Vieux (Potawatomi), raised him in a world straddling traditional Native ways and encroaching white settlement. Tragedy struck early: his twin brother died at age 9, followed by his mother and father, leading to a nomadic youth in orphanages and farms. At 16, Thorpe enrolled at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, a federal boarding school emblematic of U.S. assimilation policies under the motto "Kill the Indian, Save the Man." There, under coach Glenn "Pop" Warner, Thorpe's talents exploded. He excelled in football, track, baseball, lacrosse, and even ballroom dancing, leading Carlisle to upset victories over powerhouse teams like Harvard and Army.

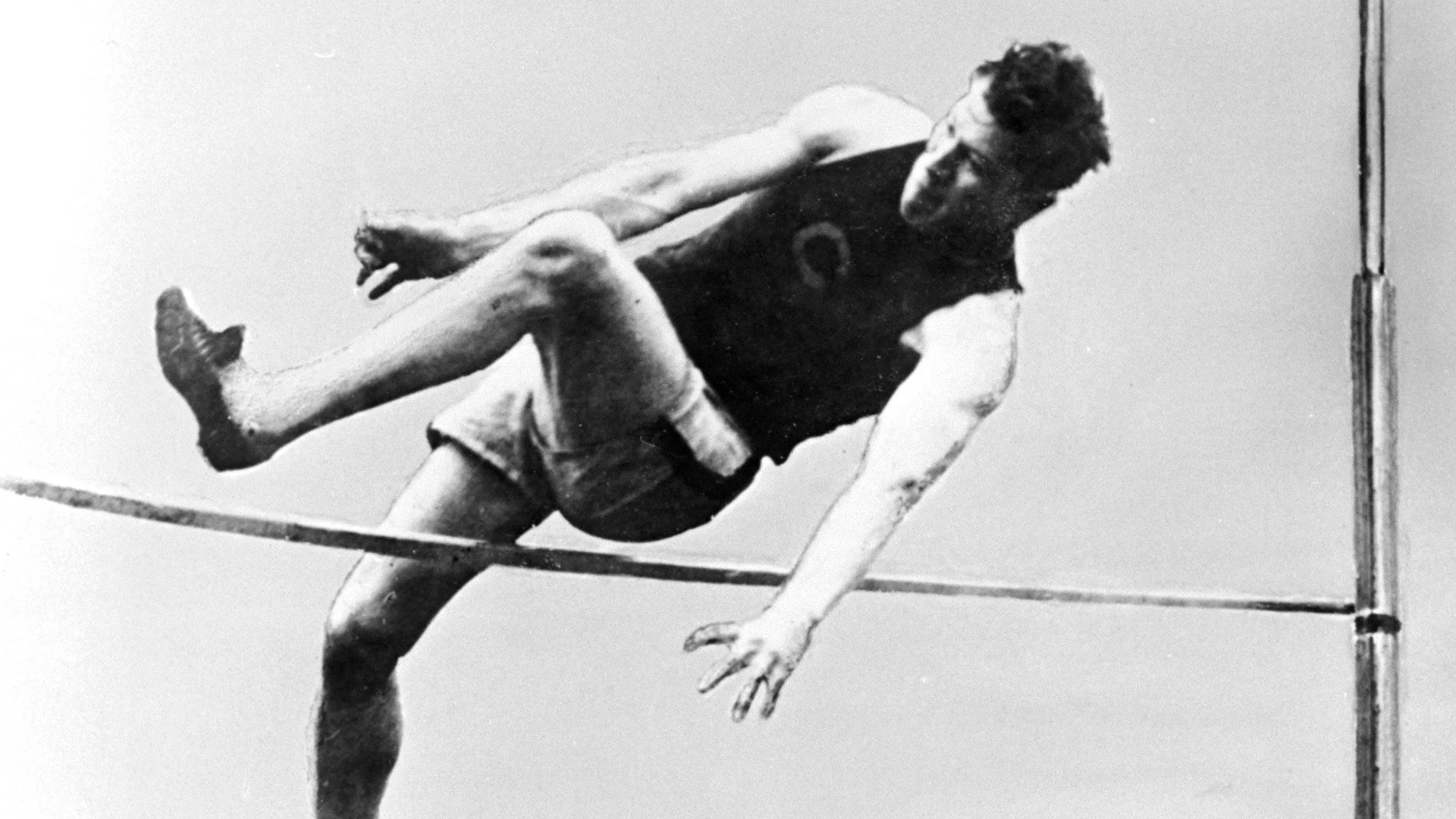

Thorpe's 1912 Olympic feats remain legendary. In the pentathlon, he won four of five events; in the decathlon, a grueling 10-event test over three days, he amassed 8,413 points—a record unbroken for nearly two decades. His versatility was unmatched: high jump, long jump, shot put, discus, javelin, pole vault, hurdles, and sprints. As the first Native American to win Olympic gold for the U.S., Thorpe challenged racial hierarchies in a time when Native peoples faced land dispossession via the Dawes Act and cultural suppression. Yet, geopolitically, his success served U.S. propaganda during the Progressive Era, showcasing American "civilizing" efforts amid imperial expansions in the Philippines and Caribbean.

Controversy soon overshadowed glory. In 1913, reports surfaced that Thorpe had played semi-professional baseball in 1909-1910 for the Rocky Mount Railroaders, earning $2 per game—a violation of amateur rules enforced by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and Amateur Athletic Union (AAU). Though common among college athletes (often under aliases), Thorpe's openness led to his medals being stripped. He returned them without protest, but the decision reeked of hypocrisy and racism; white athletes faced leniency, while Thorpe, as a Native, became a scapegoat. This mirrored broader U.S. policies: the 1887 Dawes Act fragmented tribal lands, and boarding schools like Carlisle stripped Native children of language and heritage. Thorpe's fall highlighted the double standards in American sports, a microcosm of the nation's treatment of Indigenous peoples during westward expansion and the closing of the frontier.

Undeterred, Thorpe pivoted to professional sports, becoming a multi-sport pioneer. From 1913 to 1919, he played Major League Baseball for the New York Giants, Cincinnati Reds, and Boston Braves, batting .252 over 289 games with notable power. But football was his forte. Joining the Canton Bulldogs in 1915, he led them to championships and, in 1920, helped found the American Professional Football Association (later NFL), serving as its first president. Thorpe played until 1928, also coaching and starring in barnstorming teams like the Oorang Indians, an all-Native squad that promoted Airedale dogs while showcasing Indigenous talent. His pro career intersected with the Roaring Twenties' cultural shifts: Prohibition, jazz, and the rise of mass entertainment. Thorpe's fame drew crowds, but exploitation followed—managers pocketed profits, leaving him in poverty.

To Native Americans, Thorpe was more than an athlete; he was a beacon of pride and resistance. In an era when the U.S. government sought to erase Indigenous identities—via the 1924 Indian Citizenship Act, which granted citizenship but often without voting rights—Thorpe's achievements countered stereotypes of Natives as "vanishing" or inferior. He inspired generations, from Billy Mills (Oglala Lakota, 1964 Olympic gold) to modern athletes like Jordan Marie Daniel (Kul Wicasa Lakota), who runs for Indigenous justice. Thorpe advocated for Native rights, criticizing Hollywood's portrayals and pushing for fair treatment in sports. His story reflects the geopolitical tensions of U.S. Indian policy: assimilation versus sovereignty, as tribes navigated the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 amid the Great Depression.

Thorpe's impact on American culture endures like his unbreakable records. He popularized multi-sport athleticism, influencing icons like Bo Jackson and Deion Sanders. His stripping and restoration—medals returned in 1983 (shared), fully as sole winner in 2022—sparked debates on amateurism, paving the way for professional Olympians post-1980s. Culturally, Thorpe humanized Native Americans in mainstream media: a 1951 biopic starring Burt Lancaster, though whitewashed, brought his story to millions. Towns like Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania (where he's buried after a controversial relocation), and halls of fame (Pro Football, College Football, Track and Field) honor him. In the Civil Rights era, his legacy fueled Native activism, from the American Indian Movement to modern fights over mascots and land rights.

Amid World War I's aftermath and the interwar period's isolationism, Thorpe's international success bolstered U.S. soft power, countering European athletic dominance. Posthumously, his narrative intersects with Cold War cultural diplomacy, as America touted diversity while suppressing Native voices. Today, amid reconciliation efforts—like the 2014 Native American Voting Rights Act and Land Back movements—Thorpe symbolizes resilience. Documentaries and books, such as Kate Buford's "Native American Son," explore his life's intersections with U.S. history, from Manifest Destiny to modern multiculturalism.

Thorpe's personal struggles—alcoholism, failed marriages, poverty in his later years as a laborer and bit actor—mirror the systemic challenges faced by Native communities: high unemployment, health disparities, and cultural loss. Yet, his indomitable spirit endures. In 1950, the Associated Press named him the greatest male athlete of the half-century, ahead of Babe Ruth. His legacy inspires Native youth programs, like the Jim Thorpe Games, promoting sports as empowerment.

Jim Thorpe didn't just compete; he illuminated the "Bright Path" for Native Americans and all underdogs in a nation built on contradictions. His story, woven into the fabric of U.S. sports, history, and culture, reminds us that true greatness lies in perseverance against the odds. In an era of geopolitical flux—from colonial legacies to contemporary equity fights—Thorpe's legacy stands as a testament to the enduring power of the human spirit.