Jack Johnson: The First Black Pop Culture Icon

In the early 20th century, amid the suffocating grip of Jim Crow segregation and rampant white supremacy, one man shattered barriers not just in the boxing ring but in the broader arena of American culture. Jack Johnson, the "Galveston Giant," became the first African American world heavyweight boxing champion in 1908, a title he held until 1915. But his legacy extends far beyond sports; he was the first Black pop culture icon, captivating headlines, inspiring songs, and provoking nationwide debates on race, sexuality, and power. Johnson's unapologetic defiance—flaunting wealth, dating white women, and dominating white opponents—made him a hero to Black Americans and a villain to white society. His life story, marked by triumph, scandal, and tragedy, foreshadowed the civil rights struggles to come and influenced generations of athletes and entertainers.

Born John Arthur Johnson on March 31, 1878, in Galveston, Texas, he was the third of nine children to former slaves Henry and Tina Johnson. His father worked as a janitor despite physical disabilities from the Civil War, and his mother as a dishwasher. Growing up in the impoverished 12th Ward, Johnson experienced a relatively integrated childhood, playing with white children without the rigid racial hierarchies that defined much of the South. He attended school sporadically for about five years, learning to read and write—a rarity for many Black youths then. Frail as a child, he was bullied until his mother instilled a fighting spirit, warning that schoolyard losses would earn home beatings. This tough love transformed him; by his teens, he avoided defeat in scraps. Leaving school, Johnson labored on docks, exercised horses in Dallas, and apprenticed as a carriage painter, where he first honed his boxing skills through informal bouts. At 16, he ventured to New York City, living with welterweight champion Barbados Joe Walcott and working stables, but returned to Galveston as a gym janitor, sparring with locals. His first prizefight, a beach brawl for $1.50, ignited a passion that would redefine his life.

Johnson's professional boxing career began in 1898 with a second-round knockout of Charley Brooks for the Texas State Middleweight Title. Early fights were grueling, often in illegal venues due to Texas laws. A notable 1901 loss to Joe Choynski led to jail time for both, where Choynski mentored him in defensive techniques. By 1903, with a record of nine wins, three losses, and five draws, Johnson claimed the World Colored Heavyweight Championship by defeating Denver Ed Martin on points. He defended it 12 times against top Black boxers like Sam McVey and Sam Langford, establishing dominance in the segregated "colored" circuit. His style—defensive, patient, with quick counters and a "mummy guard"—allowed him to wear down opponents while appearing effortless.

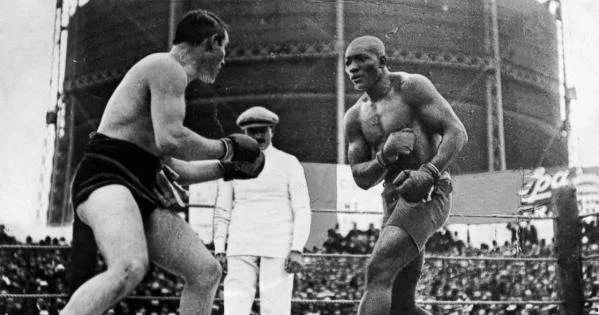

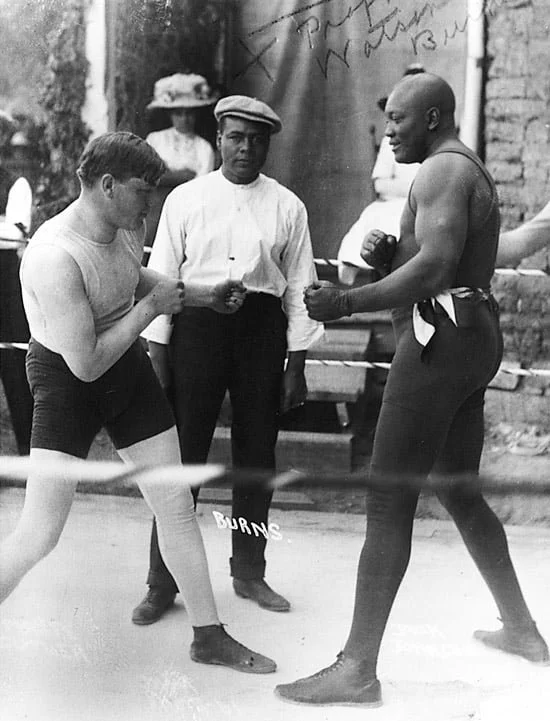

The pursuit of the world heavyweight title was fraught with racism. Champion Jim Jeffries retired undefeated in 1905, refusing to fight a Black man. Johnson chased successor Tommy Burns worldwide, finally cornering him in Sydney, Australia, on December 26, 1908. Before 20,000 spectators, Johnson dominated, taunting Burns until police stopped the fight in the 14th round, awarding him the title. This victory, amid the Progressive Era's racial tensions, sparked outrage. Novelist Jack London coined "Great White Hope," urging Jeffries' return to "wipe that golden smile from Johnson's face." Johnson defended against white challengers like Stanley Ketchel (knocked out in 1912 after a double-cross) and others, earning fortunes but fueling resentment.

The pinnacle was the "Fight of the Century" on July 4, 1910, in Reno, Nevada, against the unretired Jeffries. Billed as a racial showdown, it drew 15,000 fans and global attention. Johnson, earning $101,000 (60% of the purse), dismantled Jeffries over 15 rounds, leading to his corner throwing in the towel. Victory ignited race riots in over 50 cities, killing at least 20 and injuring hundreds. Films of the fight were banned in many states to prevent further unrest, yet it became the most viewed footage until D.W. Griffith's controversial The Birth of a Nation. Johnson's gloating and dominance symbolized Black empowerment, terrifying white supremacists who feared it challenged Social Darwinism and imperialism.

Controversies defined Johnson's reign as much as his fists. His personal life flouted Jim Crow norms: he openly dated and married white women, a direct assault on anti-miscegenation laws. Relationships with prostitutes like Belle Schreiber and Clara Kerr drew scandal. In 1911, he wed socialite Etta Terry Duryea, but abuse allegations surfaced; she committed suicide in 1912 amid infidelity and societal pressure. Mere months later, he married 18-year-old Lucille Cameron, another white woman, provoking national fury. Authorities weaponized the 1910 Mann Act, charging him with transporting women across states for "immoral purposes." Convicted by an all-white jury in 1913—despite acts predating the law—he was sentenced to a year in prison. Johnson fled to Canada, then Europe, living in exile for seven years, fighting abroad to survive.

In exile, Johnson lost his title on April 5, 1915, to Jess Willard in Havana, Cuba, after 26 rounds. He claimed it was fixed due to fatigue and age (37), but it's generally seen as legitimate. He wandered Europe, South America, and Mexico, performing exhibitions and even bullfighting. Returning in 1920, he served time at Leavenworth Federal Prison, emerging to capitalize on fame through dime museums, movie bits, and a failed wrench patent. He continued marrying white women—divorcing Lucille in 1924 for infidelity and wedding Irene Pineau in 1925, who stayed until his death. Johnson's later years included Pentecostal conversion in 1943 and fast driving, culminating in a fatal 1946 car crash at 68 after speeding from a diner that refused him service.

Johnson's cultural legacy is profound, earning him the title of first Black pop culture icon. In a racist era of Plessy v. Ferguson and limited Black visibility, he garnered more press than any Black figure, outshining leaders like Booker T. Washington. Photographed endlessly, his scandals filled front pages, blending sports with tabloid intrigue. He endorsed products, raced cars, and opened the interracial Café de Champion in Chicago, defying segregation. His unrepentant rebellion—taunting foes, ignoring critiques—inspired Black pride while inciting white backlash, delaying the next Black heavyweight title shot until Joe Louis in 1937.

Pop culture immortalized him: Lead Belly's folk song about the Titanic refusing him passage; WWI artillery shells nicknamed "Jack Johnsons"; plays like The Great White Hope (1967, adapted to film in 1970 with James Earl Jones); Ken Burns' 2005 documentary Unforgivable Blackness with Wynton Marsalis' score; albums by Miles Davis and Mos Def; and modern works like graphic novels and hip-hop tracks. Inducted into halls of fame (1954 Ring, 1990 International), he ranks among the 100 Greatest African Americans. In 2018, President Trump posthumously pardoned him, acknowledging racial injustice.

Johnson's story transcends boxing; he embodied resistance in a time when Black success was criminalized. As PBS notes, he was a "rebel of the Progressive Era," using fame to challenge white imperialism and Jim Crow. His influence echoes in Muhammad Ali's bravado and modern athletes' activism, proving sports can ignite social change. Over a century later, Jack Johnson remains a towering figure: the Galveston Giant who punched through America's color line.