Champions Divided: Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali's Stormy Alliance

In the sweltering heat of a Miami gym in 1964, two icons of Black America forged a bond that would ignite the civil rights movement and reshape sports history. Cassius Clay, the brash young boxer soon to become Muhammad Ali, stood under the tutelage of Malcolm X, the fiery Nation of Islam (NOI) minister whose words cut like a switchblade. Malcolm, seeing in Clay a vessel for Black empowerment, mentored him through his conversion to Islam and his defiance of the white establishment. Their relationship—marked by brotherhood, betrayal, and belated reconciliation—mirrored the turbulent 1960s, intersecting sports, geopolitics, religion, and culture in a narrative of resilience and regret.

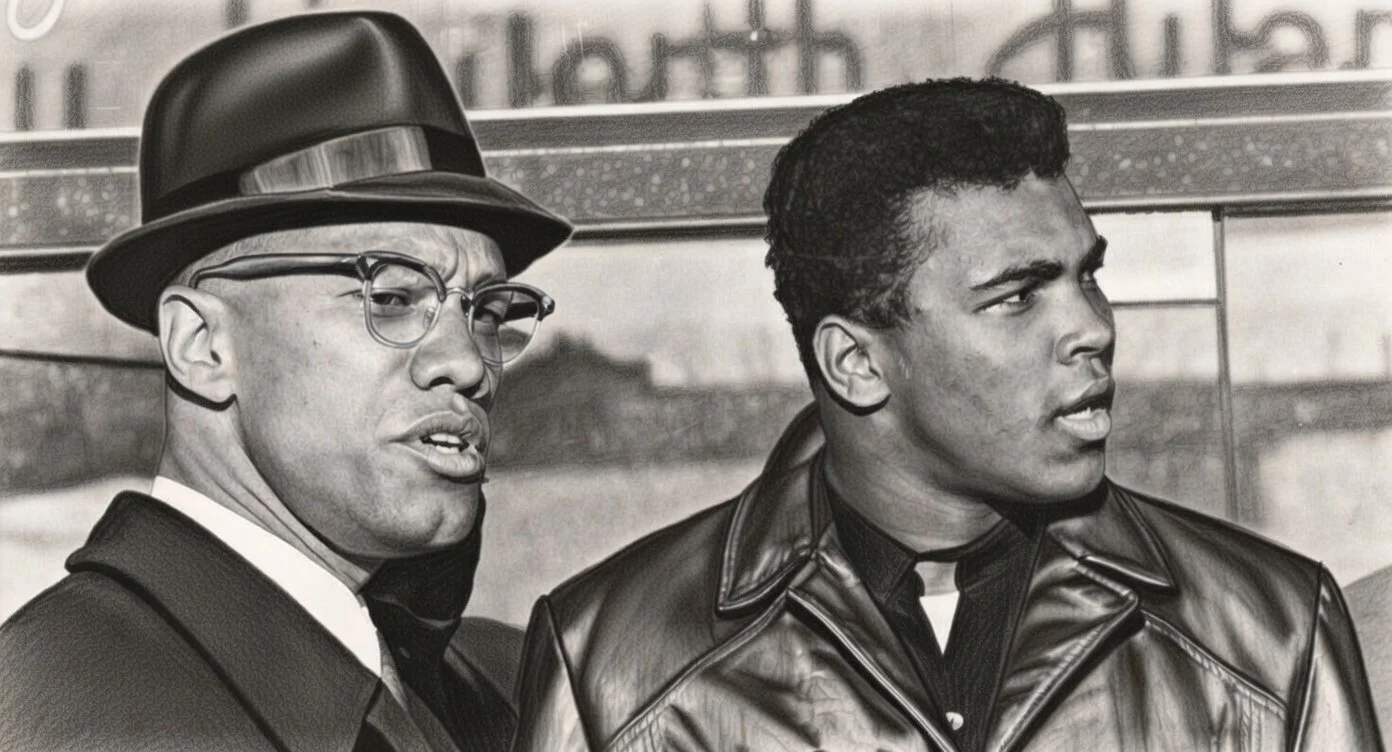

Their paths crossed in 1962, amid America's boiling racial tensions. Malcolm X, born Malcolm Little in 1925, had risen from prison to become NOI's most eloquent spokesman, advocating Black separatism and self-defense against white supremacy. Clay, born in 1942 in segregated Louisville, Kentucky, was an Olympic gold medalist (1960) whose charisma masked deep frustrations with racism. Introduced through NOI circles, Malcolm became Clay's spiritual guide, drawing him away from Christianity toward Islam. "Malcolm was my brother in faith," Ali later reflected. Their friendship deepened as Malcolm attended Clay's fights, offering counsel on everything from strategy to public persona. In February 1964, after Clay stunned the world by defeating Sonny Liston for the heavyweight title, he announced his conversion and new name: Muhammad Ali, bestowed by NOI leader Elijah Muhammad. Malcolm celebrated with him in Miami, capturing joyful photos that symbolized their alliance.

The bond was more than personal; it was political. In the geopolitics of the Cold War era, where America projected democracy abroad while suppressing Black rights at home, Malcolm and Ali challenged the status quo. Malcolm's international travels—to Africa and the Middle East—exposed him to pan-Africanism, influencing Ali's later anti-Vietnam stance. Ali, inspired by Malcolm, refused the draft in 1967, famously declaring, "I ain't got no quarrel with them Viet Cong." Their friendship amplified NOI's message, drawing young Blacks to the movement amid the civil rights struggle. Malcolm introduced Ali to his family, treating him like a son, while Ali credited Malcolm for his confidence: "He taught me to be proud of who I am." This mentorship peaked in 1964, as Malcolm helped Ali navigate fame and faith.

Yet, cracks emerged swiftly. By late 1963, Malcolm grew disillusioned with NOI after discovering Elijah Muhammad's extramarital affairs and financial improprieties—revelations that shattered his faith in the leader. Suspended for comments on John F. Kennedy's assassination ("chickens coming home to roost"), Malcolm left NOI in March 1964, founding the Organization of Afro-American Unity and embracing Sunni Islam after his Hajj pilgrimage. This defection put Ali in a bind: loyal to Elijah, who had renamed him, Ali publicly rejected Malcolm, calling him a "hypocrite" in a painful encounter in Ghana that year. Malcolm, hurt, predicted Ali's regret: "He'll realize one day." The fallout was devastating; Malcolm was assassinated on February 21, 1965, by NOI gunmen, just as Ali defended his title. Ali's silence on the murder deepened the wound.

The relationship's complexity rippled through American culture. In sports, Ali's NOI ties—fostered by Malcolm—fueled his activism, from draft resistance (leading to a 1967 ban) to his 1974 "Rumble in the Jungle" in Zaire, linking Black America to African liberation. Malcolm's influence made Ali a global symbol of resistance, intersecting with anti-colonial movements in Africa and Asia. Historically, their bond highlighted NOI's role in Black nationalism, contrasting Martin Luther King Jr.'s nonviolence. Books like "Blood Brothers" (2016) by Randy Roberts and Johnny Smith dissect this "fatal friendship," revealing how power struggles in NOI severed ties. Culturally, it inspired films, documentaries, and music—Spike Lee's "Malcolm X" (1992) nods to Ali, while Netflix's "Blood Brothers: Malcolm X & Muhammad Ali" (2021) explores their dynamic.

Reconciliation came posthumously. By the 1970s, Ali, disillusioned with NOI after Elijah's death, converted to Sunni Islam and expressed profound regret: "Turning my back on Malcolm was one of the mistakes I regret most in my life." He attended Malcolm's daughter Attallah's events, honoring his mentor. Their story endures as a cautionary tale of loyalty, betrayal, and redemption, influencing modern athletes like Colin Kaepernick, who blend sports with activism.

In a divided America, Malcolm and Ali's complex relationship reminds us of the costs of conviction—and the power of forgiveness.