Beyond the Baseline: Arthur Ashe's Legacy in Sports and Society

On July 5, 1975, under the hallowed grass of Wimbledon's Centre Court, Arthur Ashe etched his name into eternity. Facing defending champion Jimmy Connors, the 31-year-old underdog dismantled the top seed 6-1, 6-1, 5-7, 6-4, becoming the first Black man to win the prestigious title. This triumph wasn't just a sporting milestone; it was a defiant stand against racial exclusion in a sport long dominated by white elites. Arthur Ashe's life—from segregated Virginia courts to global activism—embodied resilience, influencing American culture through tennis excellence, civil rights advocacy, and a tragic battle with illness that amplified his humanitarian legacy.

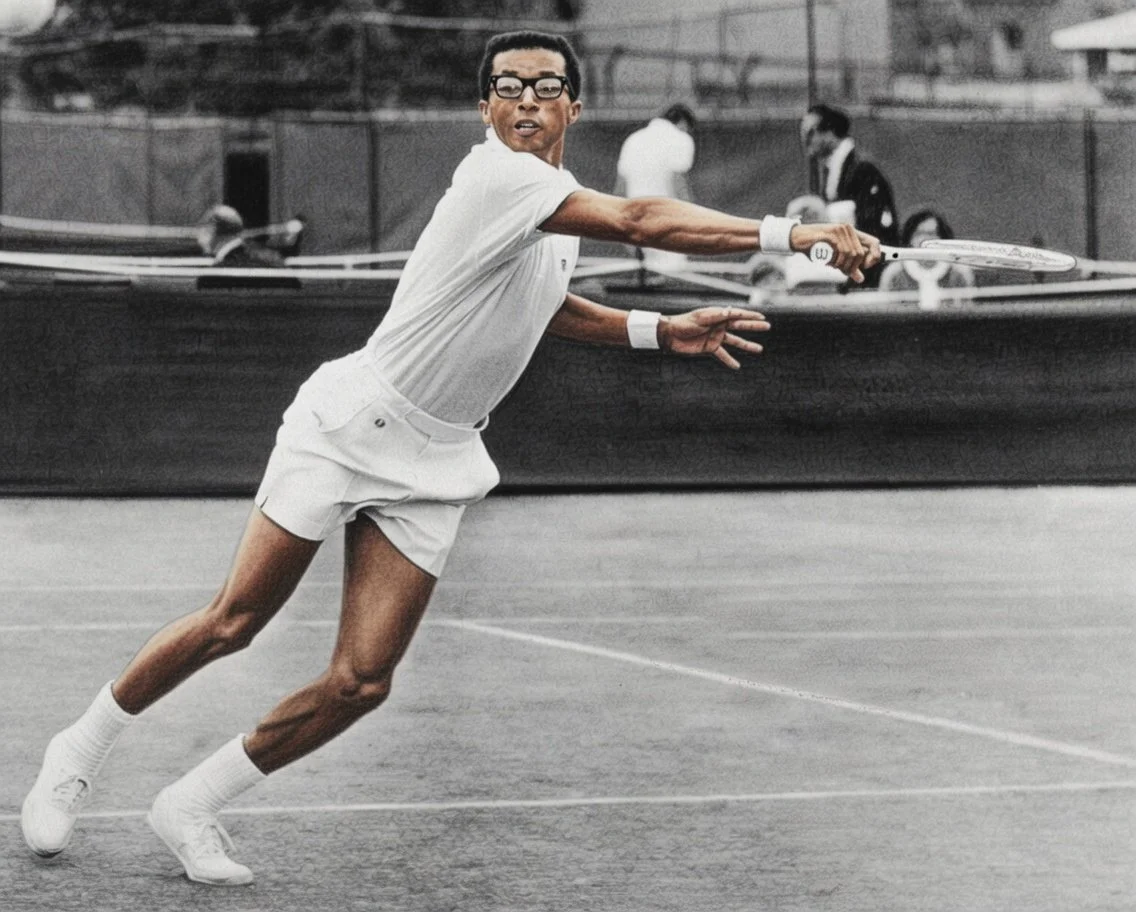

Born on July 10, 1943, in Richmond, Virginia, Arthur Robert Ashe Jr. grew up in the Jim Crow South, where segregation barred Black children from public parks and tennis clubs. Orphaned young—his mother died when he was 6, his father when he was 18—Ashe found solace in tennis, coached by Dr. Robert Walter Johnson on a Blacks-only playground court. His talent shone early: at 18, he won the National Junior Indoor Championship, becoming the first Black player to do so. At UCLA on a scholarship, he captured the 1965 NCAA singles title, the first Black man to win it. Turning pro in 1969, Ashe's accomplishments piled up: he won the 1968 US Open as an amateur (the first Black man to claim a Grand Slam), the 1970 Australian Open, and the 1975 Wimbledon. He also led the U.S. to five Davis Cup victories (1963, 1968-1970, 1975, 1978-1979), amassing a 27-5 singles record. Over his career, Ashe secured 76 titles, including 33 ATP-sanctioned ones, and reached world No. 1 in 1975. His game—marked by powerful serves, tactical acumen, and grace under pressure—redefined the sport, proving Black athletes could excel in tennis's genteel confines.

Ashe's influence on American culture extended far beyond baselines. A civil rights activist, he used his platform to combat injustice, blending sports with social change in the turbulent 1960s and 1970s. Denied a visa to apartheid South Africa in 1969 and 1970, he spearheaded boycotts, helping isolate the regime internationally. His efforts contributed to South Africa's sports ban until apartheid's end in 1991. Ashe advocated for Black athletes' rights, supporting Muhammad Ali's draft resistance and protesting unequal pay. He founded the Black Tennis Foundation to nurture minority talent and co-founded the Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP) in 1972, empowering players. Culturally, Ashe challenged stereotypes: as a Black man in a white sport, his poise and intellect countered narratives of inferiority, inspiring figures like Serena Williams and Yannick Noah. His 1973 book "A Hard Road to Glory" chronicled Black athletic history, educating generations on overlooked contributions. Amid Vietnam and Watergate, Ashe's activism mirrored broader calls for equity, influencing American discourse on race and human rights.

Tragically, Ashe's life ended prematurely due to complications from AIDS. In 1979, he suffered a heart attack, retiring in 1980. During bypass surgery in 1983, he contracted HIV from tainted blood—a common risk before widespread screening in 1985. Diagnosed in 1988, Ashe kept it private until 1992, when a USA Today reporter threatened exposure. Announcing it publicly, he became an advocate, founding the Arthur Ashe Institute for Urban Health to address disparities in minority communities. His death on November 6, 1993, at age 50 from AIDS-related pneumonia shocked the nation, humanizing the epidemic amid stigma. President Bill Clinton awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom posthumously, recognizing his dual legacy in sports and activism. Ashe's passing amplified calls for AIDS research and blood safety, influencing public health policy.

Ashe's enduring impact resonates today. Stadiums like the Arthur Ashe Stadium at the US Open (opened 1997) honor him, while his story inspires amid ongoing racial reckonings. In a polarized America, Ashe's model of quiet dignity and persistent advocacy offers lessons in bridging divides.