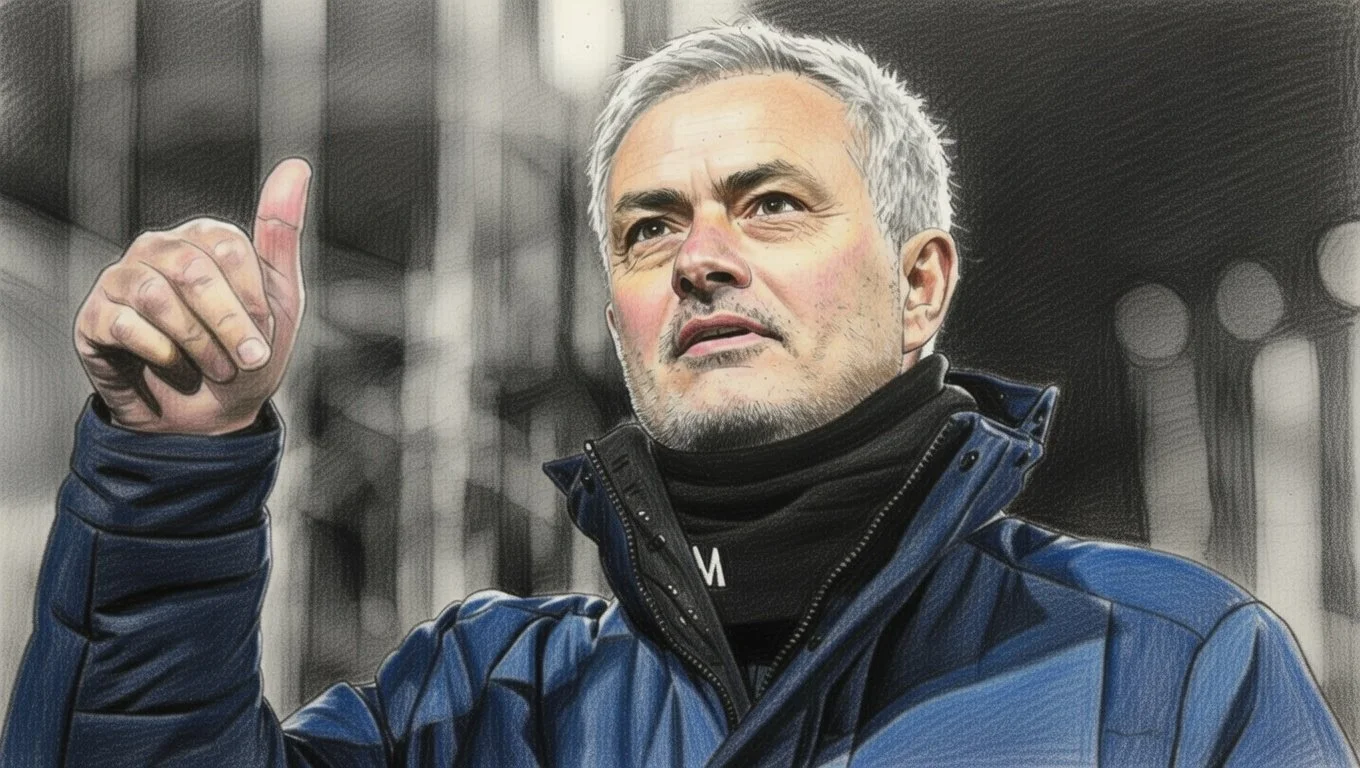

The Special One's African Affection: Why Jose Mourinho is Revered on the Continent

In the pantheon of football managers, few evoke as much passion and polarization as Jose Mourinho. The Portuguese tactician, dubbed "The Special One" after his audacious 2004 Chelsea introduction, has conquered Europe with titles at Porto, Chelsea, Inter Milan, Real Madrid, Manchester United, and Roma. Yet, his reverence in Africa transcends trophies—it's rooted in his profound bond with African players, his outspoken admiration for their qualities, and his role in elevating their careers on the global stage. Mourinho's character—charismatic, fiercely loyal, and unapologetically controversial—has endeared him to a continent where football is more than a game; it's a lifeline. Through relationships with stars like Didier Drogba, Michael Essien, and Samuel Eto'o, Mourinho has become a beloved figure, symbolizing opportunity and respect in a sport often marred by exploitation of African talent.

Mourinho's journey began in Portugal, but his affinity for African players blossomed during his managerial tenure. Born in 1963 in Setubal, he rose from translator to tactical genius, emphasizing defensive solidity and counter-attacks. His character is a blend of bravado and paternalism: he demands absolute loyalty, often clashing with club hierarchies to protect his squad, but can be ruthless with underperformers. This intensity resonates in Africa, where family and community ties are paramount. Mourinho has repeatedly praised African players for their "loyalty and purity," qualities he contrasts with what he perceives as the entitlement in European talent. In a 2024 interview, he declared, "To be honest, I love the guys and I feel that the African player is very loyal and very pure." This sentiment stems from decades of coaching Africans, whom he credits for some of his greatest successes.

The reverence starts with his transformative impact at Chelsea from 2004-2007 and 2013-2015. Mourinho assembled a squad rich in African talent, turning them into legends. Didier Drogba, the Ivorian striker signed from Marseille in 2004 for £24 million, became Mourinho's talisman. Drogba scored 164 goals in 381 appearances, leading Chelsea to two Premier League titles, four FA Cups, and the 2012 Champions League. Their bond was father-son like: Mourinho called Drogba "my son," and Drogba credited him for belief during lows. This relationship extended beyond the pitch—Mourinho supported Drogba's peace efforts in Ivory Coast's civil war, amplifying his manager's image as a mentor who cares deeply.

Similarly, Ghanaian midfielder Michael Essien, acquired from Lyon in 2005 for £24.4 million, thrived under Mourinho. Essien's versatility anchored Chelsea's midfield, contributing to multiple trophies despite injuries. Mourinho's affection is evident in anecdotes: he once joked Essien shouldn't call him "daddy" because they're nearly the same age, underscoring their close rapport. Ivorian winger Salomon Kalou, signed in 2006, also flourished, scoring 60 goals in 254 games. Mourinho's trust in these players—often starting them in big matches—demonstrated his belief in African talent, countering stereotypes of unreliability.

At Inter Milan (2008-2010), Mourinho's reverence deepened with Cameroonian striker Samuel Eto'o. Acquired in a 2009 swap for Zlatan Ibrahimovic, Eto'o scored 53 goals in 102 appearances, pivotal in Inter's 2010 Treble (Serie A, Coppa Italia, Champions League). Mourinho hailed Eto'o's adaptability, playing him out wide in the Champions League final against Bayern Munich. Their emotional embrace after the victory symbolized mutual respect. Eto'o later said Mourinho treated him "like a son," highlighting the manager's paternal style that fosters fierce loyalty.

Mourinho's time at Real Madrid (2010-2013) featured fewer Africans, but his influence persisted through players like Nigerian midfielder John Obi Mikel at Chelsea and later at other clubs. Mikel, signed in 2006 but debuting under Mourinho, played 372 games for Chelsea, winning multiple titles. Mourinho's man-management—publicly defending players amid criticism—built unbreakable bonds. This loyalty is why many African stars, like Drogba and Essien, remain vocal supporters, often attending his matches or defending him online.

Why is Mourinho so revered in Africa? It's a confluence of success, opportunity, and authenticity. Africa produces immense football talent, but many face exploitation in Europe—low wages, poor contracts, and racism. Mourinho's track record of integrating and elevating Africans challenges this. He has coached dozens from the continent, including Benni McCarthy (South Africa) at Porto, Sulley Muntari (Ghana) at Inter, and Eric Bailly (Ivory Coast) at Manchester United. His praise resonates: in a viral video, he said, "I can't go to Africa anymore! The fans there are absolutely crazy everywhere!" This stems from personal visits and charity work, like supporting Drogba's foundation for Ivorian children.

His character plays a key role. Mourinho's outspokenness—challenging referees, media, and owners—mirrors African fans' frustrations with systemic inequities. His "us vs. them" mentality aligns with underdog narratives in African football, where clubs battle richer European giants. Culturally, Mourinho's reverence boosts pride: in countries like Ivory Coast and Ghana, he's celebrated as a "father figure" to their heroes, inspiring youth academies and dreams of European success.

The impact extends to global culture. Mourinho's relationships humanize African players, countering stereotypes in media portrayals. His success with them has encouraged European clubs to scout Africa more ethically, reducing trafficking risks. In America, where soccer grows, his story influences diverse communities, paralleling NBA's international rise.

Mourinho's legacy in Africa endures. As Fenerbahce manager since 2024, he continues signing talents like Allan Saint-Maximin (French-Guinean roots). Revered as "The Special One" who sees potential where others don't, his bonds with African players cement him as a continental icon.