Hulk Hogan vs. the Iron Sheik: The Iranian-Hostage Crisis and the Rise of “Reagan-Era” Heroism

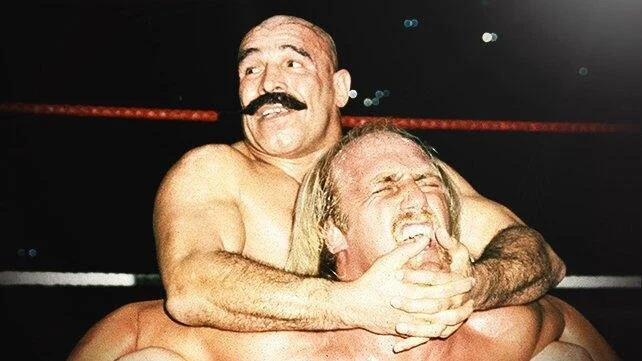

In the sweat-drenched confines of Madison Square Garden on January 23, 1984, the air crackled with more than just the anticipation of a wrestling match. As the bell rang, Hulk Hogan—hulking, blond, and draped in red, white, and blue—faced off against the Iron Sheik, a snarling Iranian heel clad in a keffiyeh and wielding a Persian club. For 5 minutes and 40 seconds, the two clashed in a spectacle that transcended the squared circle. Hogan escaped the Sheik's dreaded Camel Clutch, a move that symbolized unbreakable American resolve, before dropping his signature leg drop to pin the champion and claim the WWF World Heavyweight Championship. This wasn't mere entertainment; it was a microcosm of global politics, channeling the lingering fury of the Iranian Hostage Crisis and the triumphant heroism of Ronald Reagan's America. In an era of Cold War brinkmanship and resurgent patriotism, professional wrestling became a cultural battleground, where villains embodied foreign threats and heroes personified the American Dream.

The Iranian Hostage Crisis, which gripped the United States from November 1979 to January 1981, set the stage for this symbolic showdown. On November 4, 1979, Iranian revolutionaries stormed the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, taking 52 American diplomats and citizens hostage for 444 days. The crisis humiliated President Jimmy Carter, whose failed rescue attempt in April 1980—Operation Eagle Claw—resulted in eight American deaths and no rescues. It amplified anti-Iranian sentiment, portraying Iran under Ayatollah Khomeini as a rogue state defying Western norms. The hostages' release coincided with Reagan's inauguration on January 20, 1981, symbolizing a shift from Carter's perceived weakness to Reagan's tough-talking resolve. Reagan's administration ramped up anti-communist rhetoric, funding mujahideen in Afghanistan against Soviet invaders and labeling the USSR an "evil empire." Amid this, Iran remained a pariah, accused of sponsoring terrorism and clashing with U.S. interests in the Middle East.

Enter the Iron Sheik, born Hossein Khosrow Ali Vaziri in Tehran in 1942. A former amateur wrestler who represented Iran at the 1968 Olympics and served as a bodyguard to the Shah, Vaziri immigrated to the U.S. in the 1970s, embracing wrestling's theatricality. Under promoter Verne Gagne, he became the Iron Sheik, a villainous caricature waving the Iranian flag, spitting on American soil, and proclaiming Iran's superiority. His Camel Clutch—a submission hold twisting the opponent's back—evoked images of Middle Eastern torture, tapping into post-hostage anxieties. Just weeks before facing Hogan, on December 26, 1983, Sheik dethroned Bob Backlund for the WWF title, using underhanded tactics that fueled crowd hatred. In Reagan's America, where "Morning in America" ads promised renewal, the Sheik represented everything antithetical: foreign aggression, Islamic radicalism, and anti-Western defiance.

Hulk Hogan, born Terry Gene Bollea in 1953 in Augusta, Georgia, was the perfect foil. A bodybuilder turned wrestler, Hogan had honed his craft in the AWA before Vince McMahon Jr. poached him for WWF's national expansion. With his 24-inch pythons (biceps), bandana, and mustache, Hogan embodied Reagan-era masculinity: strong, optimistic, and unapologetically patriotic. His entrance music, "Real American," blared lyrics about fighting for rights and the American way. Hogan's promos urged kids to "train, say your prayers, and eat your vitamins," aligning with Reagan's family values and anti-drug campaigns. But beneath the heroism lurked a scripted narrative: Hogan as the defender of American honor against foreign invaders. The 1984 match was no accident; McMahon, sensing cultural currents, booked it to capitalize on anti-Iranian fervor, just as the U.S. supported Iraq in the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988), viewing Saddam Hussein as a bulwark against Khomeini.

The match itself was a geopolitical allegory wrapped in spandex. The Sheik entered to boos, swinging his club and mocking the crowd with broken English taunts like "Iran number one, USA hack-ptooie!" Hogan, met with thunderous cheers, tore his shirt in a ritual of raw power. Early dominance by the Sheik—club strikes and suplexes—mirrored Iran's initial embassy takeover, evoking American vulnerability. But Hogan's "hulking up"—shaking off pain, no-selling blows—symbolized resilience, much like Reagan's military buildup and defiant foreign policy. Escaping the Camel Clutch, a hold that had "broken" Backlund's neck in storyline, represented breaking free from hostage-like submission. The leg drop finish ignited the Garden, birthing "Hulkamania," a phenomenon that propelled WWF into mainstream culture via MTV and celebrity crossovers.

This event reflected broader American culture and politics in the 1980s. Reagan's landslide 1984 reelection rode waves of economic recovery and patriotic fervor, fueled by events like the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, where U.S. athletes dominated amid a Soviet boycott. Wrestling, under McMahon's vision, mirrored this: from regional territories to a national product, echoing America's global ascendancy. The Sheik-Hogan feud tapped into xenophobia, with crowds chanting "USA! USA!"—a precursor to post-9/11 rallies. Yet, it wasn't just jingoism; it offered catharsis for a nation scarred by Vietnam and Watergate, reaffirming heroism through scripted victories. Hogan's character aligned with neoconservative ideology, portraying America as morally superior, while villains like the Sheik (and later Nikolai Volkoff, the Soviet heel) embodied "axis of evil" precursors.

Culturally, the match accelerated wrestling's pop culture integration. Hogan hosted Saturday Night Live in 1985, starred in films like No Holds Barred (1989), and became a Reagan-era icon, even appearing at the White House. The Iron Sheik, meanwhile, parlayed his heel heat into longevity, feuding with Sgt. Slaughter in matches laden with military symbolism. This dynamic influenced American media: action films like Rambo: First Blood Part II (1985) featured lone heroes rescuing POWs from communist foes, mirroring Hogan's liberator role. Geopolitically, as U.S.-Iran relations soured further with the 1983 Beirut barracks bombing and the Iran-Contra scandal (1985-1987)—where Reagan secretly sold arms to Iran—the Sheik's persona kept the narrative alive, blending realpolitik with kayfabe.

The legacy of Hogan vs. Sheik endures as a touchstone for how sports reflect societal tensions. In post-Cold War America, wrestling evolved, but the formula persisted: foreign heels like Rusev (Russian) or Jinder Mahal (Indian-Canadian) drew heat by invoking nationalism. Hogan's fall from grace—racist remarks in 2015 leading to WWE erasure—contrasts his heroic image, highlighting the era's undercurrents of prejudice. Yet, the 1984 match remains pivotal, marking WWF's (now WWE) ascent to billion-dollar status and embedding sports entertainment in political discourse. For Iranian-Americans, the Sheik's caricature was double-edged: Vaziri, a proud Iranian who loved America, played the role for paychecks, but it fueled stereotypes amid rising Islamophobia.

In retrospect, Hogan's triumph over the Sheik wasn't just a title change; it was a cultural exorcism, purging hostage-era humiliations through athletic theater. As Reagan's America flexed its muscles globally—from Grenada invasion to Star Wars defense—the squared circle amplified the message: Heroes prevail, villains fall, and the USA stands tall. This intersection of sports, geopolitics, and culture reminds us that even in scripted battles, real-world echoes resonate loudest.