The Two-Minute War

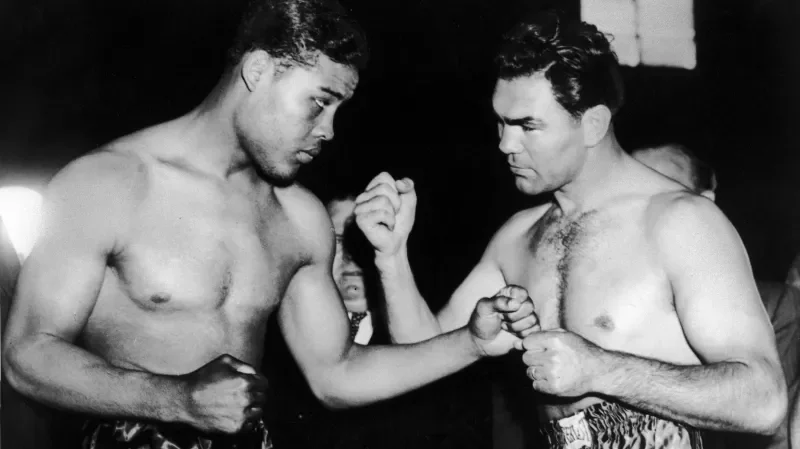

oe Louis fought Max Schmeling at Yankee Stadium, Bronx, New York, on June 22, 1938. Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images

Here's a thought experiment.

Imagine you're Joseph Goebbels, Nazi Minister of Propaganda, in the spring of 1936. Your regime has just witnessed a German boxer, Max Schmeling, knock out an undefeated Black American named Joe Louis in the 12th round at Yankee Stadium. The footage is triumphant: Schmeling's right hand landing repeatedly, Louis crumbling. You rush it into newsreels across Germany, with voice-overs proclaiming "empirical proof" of Aryan superiority. Headlines scream "Schmeling’s Fists Prove Germanic Supremacy."

You've been handed the perfect propaganda gift: a real-world demonstration in the ring that the "master race" prevails over the "inferior."

Fast-forward two years.

June 22, 1938. Yankee Stadium, New York. Over 70,000 spectators pack the seats, and an estimated 70 million Americans—half the nation's population—tune in on radio, the largest audience for any single broadcast in history up to that point.

The rematch between heavyweight champion Joe Louis and Max Schmeling.

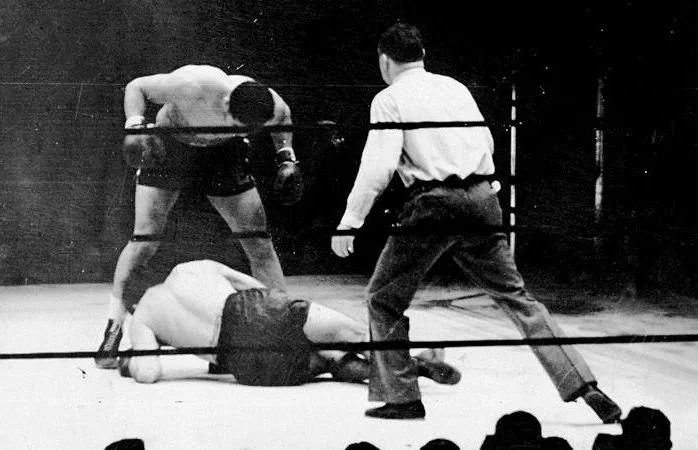

This time, it lasts exactly 124 seconds (2 minutes and 4 seconds).

Joe Louis lands 41 punches. Schmeling connects with just 2.

Schmeling hits the canvas three times. The referee stops the fight in the first round. Some ringside accounts even report hearing Schmeling cry out in pain.

In those fleeting 124 seconds, the Nazi theory of racial superiority doesn't fade quietly—it collapses with the thud of a body on canvas.

That's the strangest, most overlooked part of this story.

We assume propaganda crumbles under facts, eloquent speeches, or diplomatic pressure.

But sometimes, it shatters under a devastating left hook.

Let me unpack the hidden dynamics.

In 1936, Schmeling's upset victory fit neatly into existing prejudices. Many white Americans, comfortable with Jim Crow laws and stereotypes, believed Black fighters lacked endurance in later rounds—fading against "superior" opponents. Schmeling, a former champion studying Louis's film reels obsessively, exploited a brief drop in Louis's guard to deliver counter-rights. His 12th-round knockout confirmed biases on both sides of the Atlantic.

Nazi media exploited it ruthlessly. Although Schmeling himself was no Nazi—he never joined the party, kept his Jewish manager Joe Jacobs despite pressure, and later sheltered Jewish boys during Kristallnacht—Goebbels manufactured quotes and celebrations. Hitler invited Schmeling to lunch, gleefully watching replays. The win became "proof" of Aryan physical and mental dominance.

By 1938, the world had changed. Nazi Germany annexed Austria in the Anschluss, escalating tensions. Antisemitism raged openly. The rematch wasn't just boxing; it was a proxy battle: American democracy versus fascist tyranny, with Louis—a Black man in a segregated nation—symbolizing freedom against Schmeling, unwillingly cast as Hitler's champion.

Louis, now the heavyweight titleholder after knocking out James Braddock in 1937, trained ferociously for revenge. He vowed the fight wouldn't last long enough for Schmeling to exploit any weaknesses.

It didn't.

From the opening bell, Louis attacked relentlessly—a barrage of hooks, uppercuts, and body shots. Schmeling, backed to the ropes, was overwhelmed. The dominance was casual, almost effortless: no late-round fade, no fluke, just total supremacy.

Cognitive scientists call this "disconfirming evidence at peak emotional intensity." When deeply ingrained beliefs—racial hierarchies rooted in pseudoscience—are shattered viscerally and undeniably, they don't erode gradually; they implode.

That implosion unfolded in real time, broadcast live.

The aftermath was electric.

In Harlem, Black Americans poured into streets, hugging strangers, dancing in jubilation. Black newspapers hailed it as "the greatest day since Emancipation." For African Americans enduring lynchings, segregation, and inequality, Louis's win was cathartic—a Black hero humiliating the symbol of white supremacy.

White America shifted too. Southern newspapers, which had rooted for Schmeling in 1936, now praised "Louis Proves American Supremacy." Millions who tolerated domestic racism found the Nazi version suddenly ridiculous, exposed as hollow by one man's fists.

The victory didn't erase American racism—Louis himself faced discrimination, unable to stay in certain hotels or eat in some restaurants. But it forced cognitive dissonance: cheering a Black athlete's global triumph while denying rights at home planted seeds of change.

In Germany, Goebbels banned live broadcasts and ordered newspapers to bury the result on back pages. Too late. Smuggled footage and shortwave radio spread the news. Within weeks, Nazi claims of physical superiority became barroom jokes from Hamburg to Munich.

Schmeling, hospitalized with injuries, faded from propaganda favor. Later drafted punitively as a paratrooper, he survived the war and befriended Louis postwar.

Five months after the fight, Kristallnacht unleashed Nazi terror against Jews. Global outrage surged—but Louis's demolition had already stripped away illusions of invincibility, sharpening moral clarity against the regime.

Sports don't ignite wars.

But in the strangest twists, they can deflate the myths that fuel them—before shots are fired.

All it took was 124 seconds, one determined man, and punches that echoed worldwide.

The most sophisticated propaganda machine in history never fully recovered from that night.