From Philly Slaughterhouses to Dagestani Mountains: The Brutal Parallel of Poverty, Pride, and Combat Sports Glory

In the smoky gyms of 1970s North Philadelphia and the rugged wrestling rooms of 21st-century Dagestan, two very different places produced some of the most feared fighters the world has ever seen. One gave us Joe Frazier, Bernard Hopkins, and the cultural myth of Rocky Balboa. The other gave us Khabib Nurmagomedov, Islam Makhachev, and a pipeline of undefeated UFC champions. What connects them is not geography or era, but something deeper: extreme poverty, unbreakable family discipline, and the raw realization that combat sports offered the only realistic ladder out of generational hardship.

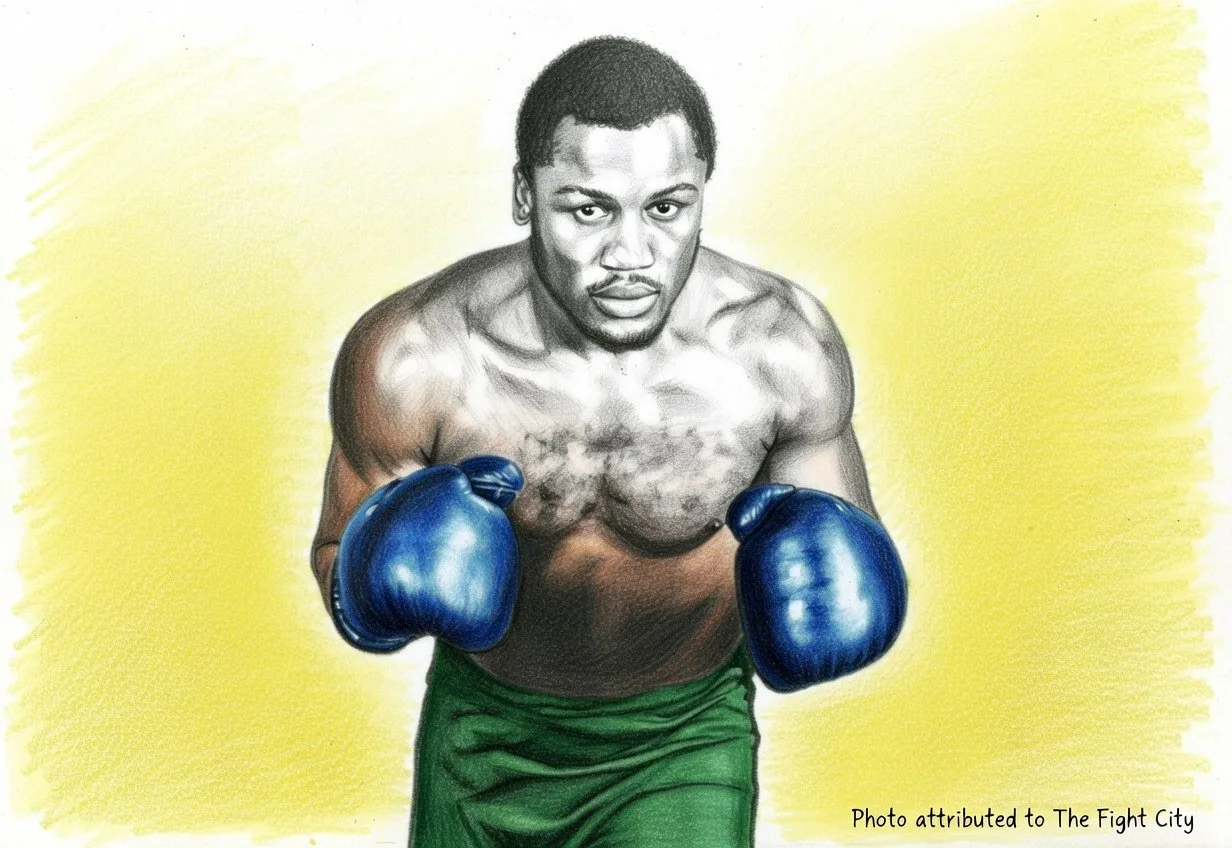

Philadelphia in the 1960s and 70s was a city of steel, slaughterhouses, and shattered dreams. Deindustrialization was already hollowing out the economy. Factories closed, jobs vanished, and neighborhoods like North Philly and Kensington became battlegrounds of gang violence, drugs, and despair. For young Black and Italian-American men, boxing gyms were sanctuaries. The Police Athletic League (PAL) on 23rd and Vine became legendary, turning street kids into champions. Joe Frazier, who arrived from South Carolina in 1959 at age 15, worked brutal shifts carrying 300-pound sides of beef in a slaughterhouse to build the strength that would later flatten Muhammad Ali. He trained at night, exhausted and hungry, because the ring was the only place where a poor kid could become somebody.

Bernard Hopkins, born in 1965 in the same tough North Philly streets, took an even darker path. By 13 he was a gang member and armed robber. At 17 he was sentenced to 18 years in prison. Behind bars he discovered boxing as salvation. Released at 25, he turned pro and became one of the greatest middleweights ever, winning titles into his 50s. Hopkins has always said boxing didn’t just save him — it gave him a purpose that the streets never could.

These stories were immortalized in Rocky (1976), the ultimate Philadelphia underdog tale. Sylvester Stallone’s character was loosely based on real Philly fighters like Frazier and Chuck Wepner. The film captured the city’s ethos: you fight because you have to, because it’s the only way to turn pain into pride.

Fast-forward half a century and 6,000 miles east to the Republic of Dagestan in southern Russia. One of the poorest regions in the Russian Federation, Dagestan is a rugged, mountainous land of ancient villages, Islamic tradition, and relentless wrestling culture. Unemployment is high, opportunities are few, and the terrain itself demands toughness. After the collapse of the Soviet Union and the brutal Chechen wars of the 1990s, many families turned to combat sports as the only viable path to a better life.

Khabib Nurmagomedov, the greatest lightweight in UFC history, is the archetype. Born in 1988 in the tiny mountain village of Sildi, he began wrestling at age eight under the strict guidance of his father, Abdulmanap. The family lived modestly — Khabib has spoken openly about eating simple food and having little money. His father, a decorated combat sambo coach, built a wrestling room in their home and drilled discipline into his son from childhood. Khabib has repeatedly said that without wrestling, he would have had “no future.” The same story repeats across Dagestan: Islam Makhachev, Khamzat Chimaev, Umar Nurmagomedov, and dozens of others emerged from similar villages, trained in the same unforgiving style, and carried the same hunger.

The societal parallels are striking. Both Philadelphia and Dagestan are places where poverty is generational and opportunities are scarce. In Philly, deindustrialization left working-class families with limited choices — factory work, crime, or the gym. In Dagestan, post-Soviet collapse, corruption, and geographic isolation created similar constraints. In both places, combat sports became the great equalizer. A kid with heart, discipline, and a good coach could rise from nothing to global stardom.

Family and community play identical roles. Frazier trained under his father’s work ethic; Khabib under his father’s iron discipline. Hopkins credits prison boxing programs; Dagestani fighters credit village wrestling rooms funded by local strongmen. In both cultures, success in the ring or cage brings immense pride to the entire community. When Frazier won the heavyweight title in 1970, North Philly celebrated like a national holiday. When Khabib defended his belt in 2018, entire villages in Dagestan shut down to watch.

The cultural narratives are almost identical. In Philadelphia, boxing represented the triumph of the underdog — the Italian immigrant, the Black migrant from the South, the kid who refused to stay down. In Dagestan, MMA represents the same: the mountain warrior who refuses to be defined by poverty or politics. Both are deeply masculine cultures where toughness is currency and loyalty is everything. Both produced fighters who carry their people’s pride on their shoulders.

What makes these stories timeless is the universal truth they reveal: in places where the system offers few paths, combat sports become the ultimate meritocracy. Talent, work ethic, and pain tolerance are the only requirements. No college degree needed. No connections required. Just the willingness to bleed in the gym every single day.

Today, Philadelphia’s boxing gyms are quieter, though the spirit lives on in fighters like Jaron “Boots” Ennis. Dagestan’s wrestling rooms are busier than ever, feeding a seemingly endless pipeline to the UFC. The environments are different — one urban and industrial, the other rural and mountainous — but the equation is the same: hardship + discipline + combat sports = a way out.

From the slaughterhouse floors of North Philly to the mountain villages of Dagestan, the message is clear: when society offers no easy dreams, the hardest fighters find their own.