Playing Go Against the Dragon: How the Ancient Chinese Game Shapes US Strategy Toward China

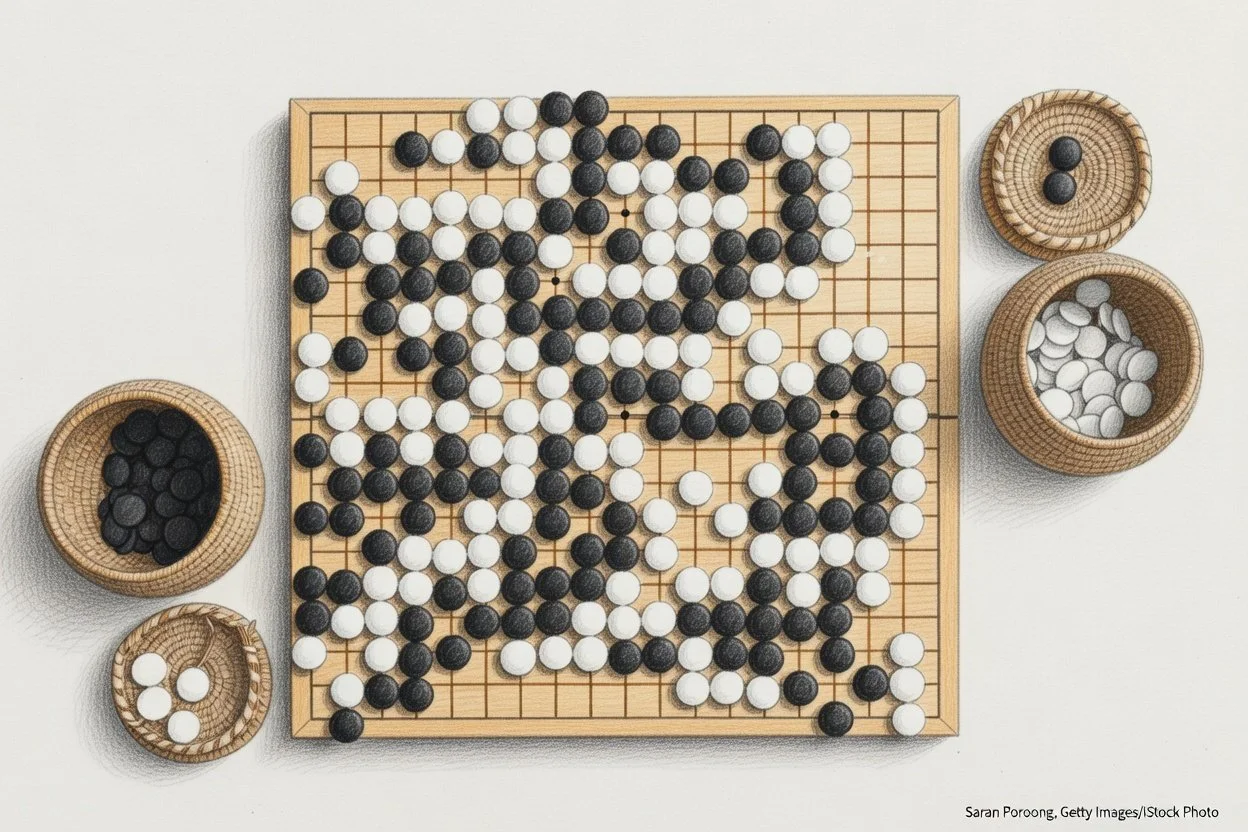

Imagine a vast 19x19 grid, where black and white stones are placed not to annihilate an opponent's king, but to encircle territory, build influence, and patiently outmaneuver over hundreds of moves. This is Go—weiqi in Chinese—an ancient board game dating back 2,500 years, revered as the ultimate test of strategic depth. While chess demands decisive attacks and material superiority, Go rewards subtlety: control key points (tè), form flexible shapes, and erode your rival's position without direct confrontation. Henry Kissinger famously noted that Americans play chess—seeking checkmate—while Chinese play Go, prioritizing encirclement and long-term dominance. In the escalating US-China rivalry, this analogy is no mere metaphor. By adopting Go's principles, the United States can craft a sustainable strategy to counter Beijing's ascent, focusing on patient containment, alliance networks, and economic strangulation rather than risky frontal assaults.

Go's essence lies in balance and influence. Players alternate placing stones to claim territory by surrounding empty space and enemy groups. Capturing occurs indirectly—cut off liberties (adjacent empty points)—and overextension invites disaster. The endgame favors the player with the most controlled board, not the boldest strikes. China embodies this: its grand strategy, rooted in Sun Tzu's "Art of War" and weiqi philosophy, emphasizes "shi" (positional advantage) through gradual expansion. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), launched in 2013, exemplifies this: over $1 trillion invested in 150+ countries' infrastructure, creating debt dependencies and port access from Pakistan's Gwadar to Sri Lanka's Hambantota. Like Go stones forming eyes (secure bases), BRI secures economic encirclement, giving China leverage without firing a shot.

In the South China Sea, Beijing's "nine-dash line" mirrors Go's invasion of weak groups: artificial islands on reefs claim 90% of contested waters, militarized with runways and missiles, choking vital trade routes ($3.4 trillion annually). Taiwan faces similar pressure: "gray zone" tactics—daily incursions, economic coercion—build influence without full invasion, testing US resolve like probing liberties. Africa's mineral-rich nations fall under BRI "strings," securing rare earths for EVs and tech dominance. This weiqi mastery avoids chess-like blunders: no direct wars, just inexorable gains.

The US, conversely, has played chess: bold moves like Trump's tariffs (escalating to 100% on EVs in 2025) seek quick "checkmates" but invite retaliation, disrupting supply chains without altering the board. Military pivots—freedom-of-navigation ops in the South China Sea—project power but risk escalation, overextending like a failed Go ladder. Biden's CHIPS Act ($52 billion) and Inflation Reduction Act subsidize reshoring, but China's overcapacity floods markets, eroding gains. This directness cedes initiative, as Beijing responds with patience.

To counter, America must embrace Go: encircle via influence networks. The Quad (US, Japan, India, Australia) and AUKUS form a Pacific "net," mirroring moyo (large potential territory). Expand to include Philippines, Vietnam—key choke points. Tech decoupling—banning Huawei, TSMC fabs in Arizona—cuts liberties in semiconductors, where China lags despite $150 billion investments. Economic "ko fights": targeted sanctions on BRI debtors, offering alternatives like PGII ($600 billion pledged).

Energy encirclement: US LNG exports flooded Europe post-Ukraine, reducing Russia's leverage; replicate against China via allies' renewables and Australian critical minerals. Diplomatically, court Global South: debt relief swaps for non-BRI alignment, echoing Marshall Plan's Go-like spread.

Historical precedents abound. Cold War containment—Truman Doctrine, NATO—was weiqi: encircling Soviet influence without invasion until collapse. Britain's "Great Game" against Russia encircled via India, Afghanistan proxies. China itself used Go in Tibet, Xinjiang: gradual Sinicization via migration, infrastructure.

Adopting weiqi demands patience: avoid Taiwan "ladders" risking capture; build "thickness" in alliances. RAND reports urge this shift: "Go favors the patient strategist." Politically, it counters domestic war fatigue—chess invites quagmires like Afghanistan.

In 2026, with Taiwan tensions and BRI debt traps, US must pivot. Train strategists in weiqi (as some military academies do). Victory lies not in checkmate, but controlling the board—suffocating China's ambitions through encirclement.

As Kissinger warned: "In Go, the skilled player leaves room for flight." US must deny that room, securing a multipolar future on its terms.