From American Import to National Passion: The Introduction and Growth of Baseball in Japan

Imagine a Tokyo schoolyard in 1872, where a young American teacher named Horace Wilson gathers curious Japanese students around a strange leather ball and wooden bat, demonstrating swings and throws under the watchful eyes of a nation newly opened to the West. This modest lesson, amid the Meiji Restoration's whirlwind of modernization, plants the seed of what would become Japan's enduring love affair with baseball—a game imported from America that survived imperial ambitions, wartime bans, and post-war occupation to blossom into a cultural institution rivaling sumo. For military history enthusiasts tracing cultural exchanges in empire-building and sports fans marveling at global diffusion, Japan's baseball story isn't mere recreation; it's a testament to how a foreign pastime can root deeply, adapt, and thrive, even through the fires of conflict and reconciliation.

Baseball arrived in Japan during the Meiji era (1868-1912), a time of rapid Westernization as the nation shed feudal isolation to compete with global powers. Horace Wilson, an American instructor at Kaisei Gakko ( precursor to Tokyo University), introduced the game in 1872, teaching rules and equipment to students eager for modern pursuits. By 1878, the first organized team formed at Shimbashi Athletic Club, and college rivalries like Waseda vs. Keio emerged in the 1890s, drawing crowds and fostering school spirit. American missionaries, teachers, and engineers fueled early growth: Albert Bates organized tours, while U.S. Navy visits brought exhibition games. The game's emphasis on discipline, teamwork, and strategy resonated with samurai values transitioning to modern society, making it a perfect fit for Japan's industrialization drive. By the early 1900s, high school tournaments like Koshien (started 1915) became national obsessions, with dramatic underdog stories mirroring bushido ideals of perseverance.

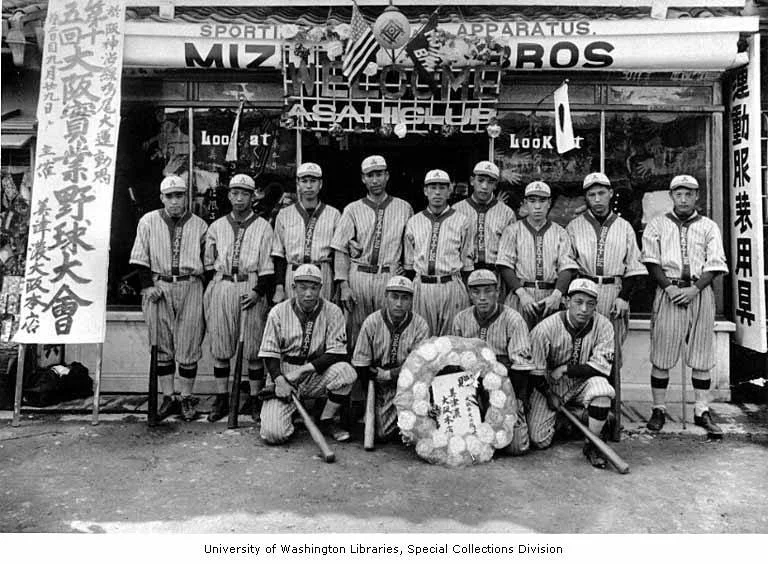

The interwar years saw explosive expansion, heavily influenced by American pros. The pinnacle was Babe Ruth's 1934 all-star tour, organized by newspaper magnate Matsutaro Shoriki. Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and stars like Jimmie Foxx played 18 games across Japan, drawing over 500,000 fans—Ruth hit 13 homers, but the real impact was inspirational. Crowds mobbed stations, schoolgirls fainted, and the tour birthed Japan's first professional league in 1936, the Japanese Baseball League (JBL), with teams like the Yomiuri Giants founded by Shoriki. American-style barnstorming and coaching refined techniques: players adopted sliding, curveballs, and scouting. Growth was meteoric—attendance soared, radio broadcasts popularized stars like Eiji Sawamura (who struck out Ruth, Gehrig, and Foxx in an exhibition), and baseball symbolized Japan's rising modernity amid militarism.

But World War II brought brutal interruption. As tensions escalated, baseball faced increasing restrictions. English terms were banned in 1940 ( "strike" became "yoshi," "ball" "dame"), and foreign influences purged to promote "pure" Japanese spirit. By 1943, pro leagues suspended amid resource shortages and bombings; many players drafted, including Sawamura, killed in 1944 when his ship sank. Games continued sporadically for morale—factory teams played, military units organized matches—but the sport symbolized enemy culture. Propaganda portrayed it as decadent Americanism, yet underground enthusiasm persisted, with kids using makeshift equipment.

Post-surrender in 1945, baseball's revival became a cornerstone of U.S. occupation strategy under MacArthur, who viewed it as democratic therapy. Leagues resumed informally in 1946, fully professional by 1950 with two leagues (Central and Pacific). American tours accelerated growth: Lefty O'Doul's 1949 San Francisco Seals drew massive crowds, teaching techniques and fostering goodwill. Subsequent visits by Joe DiMaggio (1950), Willie Mays, and full MLB all-stars in the 1950s integrated styles—Japanese adopted power hitting while retaining small-ball precision. Stars like Sadaharu Oh (868 career homers) emerged, blending influences. Attendance exploded, Koshien became a cultural rite, and NPB rivaled MLB in talent depth.

Baseball's wartime survival and post-war boom reflected Japan's resilience. Banned yet beloved underground, it reemerged stronger, symbolizing normalcy amid reconstruction. U.S. influence—tours, coaching, equipment—hybridized the game: high school emphasis on spirit (ganbaru), pro focus on harmony. Today, NPB thrives with 12 teams, global stars like Shohei Ohtani, and WBC victories (2006, 2009, 2023).

Japan's baseball journey—from Meiji import to wartime shadow to post-war phoenix—illustrates cultural adaptation's power, turning an American game into a Japanese soul. It bridged enemies through shared joy, growing despite conflict. But as global sports homogenize, one wonders: Can such organic cultural fusions still emerge in today's world?