The Midshipman Who Came in from the Cold

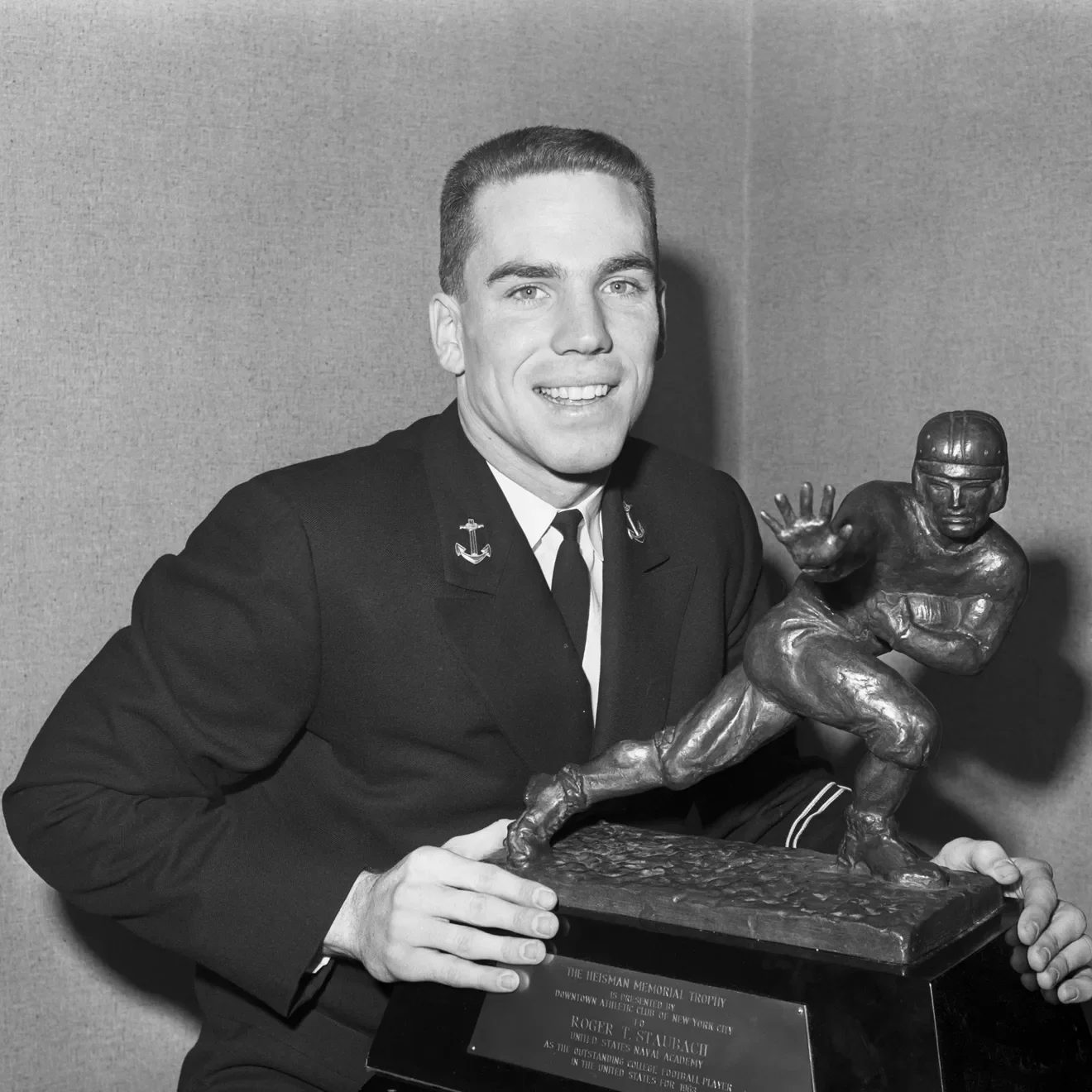

There are quarterbacks, and then there is Roger Staubach, a man who spent four prime years of his life counting crates of 5.56 ammo on a rust-streaked LST in the Mekong Delta before he ever took a snap for pay. I have seen many curious specimens in my time (Joe Louis in a Pompton Lakes training camp, Man o’ War at Saratoga, Jack Dempsey shadow-boxing in a Broadway gym), but I have never seen a more improbable champion than this soft-spoken ensign who walked out of the Navy in 1969 carrying a Heisman Trophy in one seabag and a Bronze Star in the other.

Picture it: the way a fight chronicler must: 1964, the Dallas Cowboys select a 22-year-old Annapolis junior in the tenth round of the future draft (yes, the tenth; even Tom Landry, that austere Presbyterian, could not foresee what the gods had in store). The kid wins the Heisman the next year, graduates, kisses his bride, and disappears into the brown-water Navy. Four years later, older than most rookies by half a decade, he reports to camp looking like a recruiting poster that learned to read defenses. The shoulders are still square, the eyes still clear, but there is something new behind them: the knowledge that men have died on his watch because a pallet of beans arrived six hours late. That sort of knowledge tends to concentrate the mind when fourth-and-seven stares you in the face.

Cincinnati native and Purcell grad Roger Staubach became the first to win the Heisman Trophy and be named Super Bowl MVP. Take a look at his impressive career, in photos.

September 1963: Navy Midshipmen quarterback Roger Staubach in action.

Malcolm Emmons/USA TODAY Sports

I watched him in 1971, the year he finally wrested the job from Craig Morton. Landry ran a system as complicated as the Navy’s fire-control tables, yet Staubach absorbed it the way a destroyer absorbs a following sea: without complaint, without visible effort. The first time I saw him scramble (those quick, economical steps, the sudden cut like a ship altering course to avoid a torpedo), I understood. This was not a quarterbacking; it was seamanship translated into cleats.

He gave the Cowboys something no playbook could diagram: the calm of a man who had already been shot at. When the pocket collapsed, when the Vikings or the Dolphins brought the house, Staubach did not flinch. He simply executed the way he had once executed supply runs under monsoon fire: eyes up, options weighed, decision made. Twenty-three fourth-quarter comebacks in nine seasons as a starter. Twenty-three. That is not luck; that is the residue of having kept cooler heads alive in Chu Lai.

The statistics are familiar now (two Super Bowl rings, the Hail Mary, the nickname “Captain Comeback”), but numbers never tell the whole story. The story is the way he carried himself: polite in victory, courteous in defeat, never a boast, never a curse. In an era when professional athletes began to resemble rock stars more than midshipmen, Staubach remained the only what he had always been: an officer doing his duty, whether the duty happened to be moving chains or moving the football.

I covered wars and prize fights long enough to know that genuine courage is quiet. It does not preen. It does not need a microphone. It simply shows up on time, does the job, and lets history keep the score. Roger Staubach did that for nine seasons in Dallas, and he did it wearing the same expression he must have worn when the klaxon sounded general quarters somewhere off the Paracel Islands.

There have been greater pure passers, greater pure runners, greater pure anything-you-like. But there has never been another quarterback who arrived already tempered by four years of real stakes, who treated every Sunday as if it were merely another watch on the bridge. The Navy gave us many things (carriers, submarines, and the occasional admiral who could quote Thucydides), but its finest gift to American sport was a 27-year-old rookie Roger Staubach, who proved that a man can serve his country in uniform and still serve it just as honorably in shoulder pads.

And when he retired, still upright at thirty-seven, he left behind not just trophies but a standard: that the highest form of leadership is the kind that asks nothing of others it has not already asked of itself.

One wonders, in this age of guaranteed contracts and TikTok celebrations, whether the game will ever again produce a champion quite so improbably, and quietly, heroic.